As we close out 2012, and embark upon a new set of challenges in 2013, this week’s EBRIef offers a roundup of our 2012 research. Best wishes for a Happy and Prosperous New Year!

Share EBRIef with your friends and colleagues – and let them know they can sign up for their own copy HERE

What’s New(s) – Health & Workforce

“Findings from the 2012 EBRI/MGA Consumer Engagement in Health Care Survey” MORE.

"Views on Employment-Based Health Benefits: Findings from the 2012 Health Confidence Survey" MORE.

“Self-Insured Health Plans: State Variation and Recent Trends by Firm Size” MORE.

'Savings Needed for Health Expenses for People Eligible for Medicare: Some Rare Good News,' and 'IRA Asset Allocation, 2010' MORE.

Employment-Based Retiree Health Benefits: Trends in Access and Coverage, 1997-2010” MORE.

“Sources of Health Insurance and Characteristics of the Uninsured: Analysis of the March 2012 Current Population Survey” MORE.

"2012 Health Confidence Survey: Americans Remain Confident About Health Care, Concerned About Costs, Following Supreme Court Decision" MORE.

"Satisfaction With Health Coverage and Care: Findings from the 2011 EBRI/MGA Consumer Engagement in Health Care Survey" MORE.

“Private Health Insurance Exchanges and Defined Contribution Health Plans: Is It Déjà Vu All Over Again?” MORE.

'Health Plan Choice: Findings from the 2011 EBRI/MGA Consumer Engagement in Health Care Survey' MORE.

'Use of Health Care Services and Access Issues by Type of Health Plan: Findings from the EBRI/MGA Consumer Engagement in Health Care Survey' MORE.

"Trends in Employment-Based Coverage Among Workers, and Access to Coverage Among Uninsured Workers, 1995-2011" MORE.

'Characteristics of the Population With Consumer-Driven and High-Deductible Health Plans, 2005–2011' MORE.

“Employment-Based Health Benefits: Trends in Access and Coverage, 1997-2010” MORE.

‘Trends in Health Coverage for Part-Time Workers’ MORE.

'Employer and Worker Contributions to Health Savings Accounts and Health Reimbursement Arrangements, 2006–2011' MORE.

“Health Savings Accounts and Health Reimbursement Arrangements: Assets, Account Balances, and Rollovers, 2006–2011” MORE.

'The Impact of PPACA on Employment-Based Health Coverage of Adult Children to Age 26' MORE.

“Findings from the 2012 EBRI/MGA Consumer Engagement in Health Care Survey” MORE.

"Views on Employment-Based Health Benefits: Findings from the 2012 Health Confidence Survey" MORE.

“Self-Insured Health Plans: State Variation and Recent Trends by Firm Size” MORE.

'Savings Needed for Health Expenses for People Eligible for Medicare: Some Rare Good News,' and 'IRA Asset Allocation, 2010' MORE.

Employment-Based Retiree Health Benefits: Trends in Access and Coverage, 1997-2010” MORE.

“Sources of Health Insurance and Characteristics of the Uninsured: Analysis of the March 2012 Current Population Survey” MORE.

"2012 Health Confidence Survey: Americans Remain Confident About Health Care, Concerned About Costs, Following Supreme Court Decision" MORE.

"Satisfaction With Health Coverage and Care: Findings from the 2011 EBRI/MGA Consumer Engagement in Health Care Survey" MORE.

“Private Health Insurance Exchanges and Defined Contribution Health Plans: Is It Déjà Vu All Over Again?” MORE.

'Health Plan Choice: Findings from the 2011 EBRI/MGA Consumer Engagement in Health Care Survey' MORE.

'Use of Health Care Services and Access Issues by Type of Health Plan: Findings from the EBRI/MGA Consumer Engagement in Health Care Survey' MORE.

"Trends in Employment-Based Coverage Among Workers, and Access to Coverage Among Uninsured Workers, 1995-2011" MORE.

'Characteristics of the Population With Consumer-Driven and High-Deductible Health Plans, 2005–2011' MORE.

“Employment-Based Health Benefits: Trends in Access and Coverage, 1997-2010” MORE.

‘Trends in Health Coverage for Part-Time Workers’ MORE.

'Employer and Worker Contributions to Health Savings Accounts and Health Reimbursement Arrangements, 2006–2011' MORE.

“Health Savings Accounts and Health Reimbursement Arrangements: Assets, Account Balances, and Rollovers, 2006–2011” MORE.

'The Impact of PPACA on Employment-Based Health Coverage of Adult Children to Age 26' MORE.

What’s New(s) – Retirement

“401(k) Plan Asset Allocation, Account Balances, and Loan Activity in 2011” MORE.

"Employee Tenure Trends, 1983–2012" MORE.

“All or Nothing? An Expanded Perspective on Retirement Readiness” MORE.

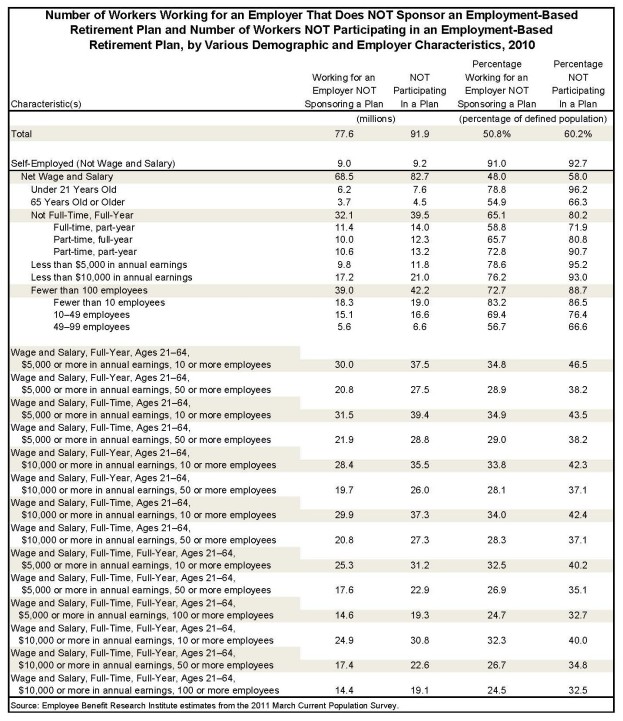

“Employment-Based Retirement Plan Participation: Geographic Differences and Trends, 2011” MORE.

'IRA Asset Allocation, 2010' MORE.

“Individual Account Retirement Plans: An Analysis of the 2010 Survey of Consumer Finances” MORE.

"Increasing Default Deferral Rates in Automatic Enrollment 401(k) Plans: The Impact on Retirement Savings Success in Plans With Automatic Escalation" MORE.

"Is Working to Age 70 Really the Answer for Retirement Income Adequacy?" MORE.

““After” Math: The Impact and Influence of Incentives on Benefit Policy” MORE.

'Own-to-Rent Transitions and Changes in Housing Equity for Older Americans' MORE.

'Retirement Readiness Ratings and Retirement Savings Shortfalls for Gen Xers: The Impact of Eligibility for Participation in a 401(k) Plan' MORE.

“Effects of Nursing Home Stays on Household Portfolios” MORE.

“Individual Retirement Account Balances, Contributions, and Rollovers, 2010: The EBRI IRA DatabaseTM” MORE.

"Retirement Income Adequacy for Boomers and Gen Xers: Evidence from the 2012 EBRI Retirement Security Projection Model®" MORE.

'Time Trends in Poverty for Older Americans Between 2001–2009' MORE.

‘Modifying the Federal Tax Treatment of 401(k) Plan Contributions: Projected Impact on Participant Account Balances’ MORE.

“The 2012 Retirement Confidence Survey: Job Insecurity, Debt Weigh on Retirement Confidence, Savings” MORE.

'Labor-force Participation Rates of the Population Age 55 and Older, 2011: After the Economic Downturn' MORE.

“Expenditure Patterns of Older Americans, 2001-2009” MORE.

'Spending Adjustments Made By Older Americans to Save Money' MORE.

“401(k) Plan Asset Allocation, Account Balances, and Loan Activity in 2011” MORE.

"Employee Tenure Trends, 1983–2012" MORE.

“All or Nothing? An Expanded Perspective on Retirement Readiness” MORE.

“Employment-Based Retirement Plan Participation: Geographic Differences and Trends, 2011” MORE.

'IRA Asset Allocation, 2010' MORE.

“Individual Account Retirement Plans: An Analysis of the 2010 Survey of Consumer Finances” MORE.

"Increasing Default Deferral Rates in Automatic Enrollment 401(k) Plans: The Impact on Retirement Savings Success in Plans With Automatic Escalation" MORE.

"Is Working to Age 70 Really the Answer for Retirement Income Adequacy?" MORE.

““After” Math: The Impact and Influence of Incentives on Benefit Policy” MORE.

'Own-to-Rent Transitions and Changes in Housing Equity for Older Americans' MORE.

'Retirement Readiness Ratings and Retirement Savings Shortfalls for Gen Xers: The Impact of Eligibility for Participation in a 401(k) Plan' MORE.

“Effects of Nursing Home Stays on Household Portfolios” MORE.

“Individual Retirement Account Balances, Contributions, and Rollovers, 2010: The EBRI IRA DatabaseTM” MORE.

"Retirement Income Adequacy for Boomers and Gen Xers: Evidence from the 2012 EBRI Retirement Security Projection Model®" MORE.

'Time Trends in Poverty for Older Americans Between 2001–2009' MORE.

‘Modifying the Federal Tax Treatment of 401(k) Plan Contributions: Projected Impact on Participant Account Balances’ MORE.

“The 2012 Retirement Confidence Survey: Job Insecurity, Debt Weigh on Retirement Confidence, Savings” MORE.

'Labor-force Participation Rates of the Population Age 55 and Older, 2011: After the Economic Downturn' MORE.

“Expenditure Patterns of Older Americans, 2001-2009” MORE.

'Spending Adjustments Made By Older Americans to Save Money' MORE.