Several weeks back, my wife and I sat down with a financial planner to review and update our financial plans. Doing so brought with it a bit of personal trepidation since, being “in the business” I not only had a working knowledge of what needed to be done, I also had a pretty good sense of what hadn’t been done, and what hadn’t been done the way it should have been done in some time. As I surrendered copies of the statements from my three separate 401(k) accounts, rollover IRA, traditional IRA, and SEP-IRA, I found myself wondering (again) why I hadn’t gotten around to consolidating some of those accounts.

More and more Americans are finding themselves with multiple savings accounts, not only because of the relatively consistent pattern of job change in the American economy (see “Tenure, Tracked”), but because those job changes frequently result in rollovers to individual retirement accounts. On the other hand, in recent years, it has gotten easier to simply leave your 401(k) with a prior employer’s plan, and, with the convenience of online access and/or call center support, and the allure of inertia, many have surely opted to forestall, if not postpone the decision.

Those decisions have, of course, made it harder to assess the true accumulations in these plans. Indeed, today’s “average” 401(k) calculation suffers not only from being an average of widely varied tenure and age components, it increasingly represents the average of those balances with only a current employer plan.

But if you’re an individual worried about keeping up with all those accounts―or a regulator or policymaker concerned about the growing complexity of that task for those individuals―you might well wonder how those accounts are being managed? Are the investment allocations in those IRAs different from that of the 401(k)s?

New EBRI research (see “Retirement Plan Participation and Asset Allocation, 2010”) reveals that, in addition to demographic factors related to family heads, asset allocation within a family head’s retirement plan does seem to be affected by his or her ownership of other types of retirement plans.

According to the research, which was based on estimates from the Federal Reserve’s 2010 Survey of Consumer Finances,¹ those who own an IRA are more likely to be invested all in stocks if they also own a 401(k)-type of plan, and those who own a defined benefit (DB) plan and a 401(k)-type plan are also less likely to allocate the investments of that defined contribution plan to all interest-earning assets. Moreover, those family heads who are invested more heavily in stocks in their 401(k)-type plan and also own an IRA have a high probability of also being heavily invested in stocks in their IRA.

The bottom line? Participants in these plans generally invest them in similar manners, although some participants did have significantly different allocations across the two plan types. What we don’t know is if those similarities―and differences―are the result of conscious choice based on an awareness of these various plans, a consequence of investments in target-date or balanced funds, or mere coincidence.

Nevin E. Adams, JD

¹ It is worth noting that, while these results provide important information on behavior within retirement savings plans, it is self-reported data from a survey of a small sample of respondents, and does not include the type of detail on asset allocation within 401(k) plans that is provided by the EBRI/ICI Participant-Directed Retirement Plan Data Collection Project or on IRAs that is provided by the EBRI IRA Database. However, these results do provide some evidence of how participants who own both types of retirement plans allocate their assets among both types of plans, and this can be evaluated with future results from the combined IRA and 401(k) database that EBRI is currently completing.

this blog is about topics of interest to plan advisers (or advisors) and the employer-sponsored benefit plans they support. *It doesn't have a thing to do (any more) with PLANADVISER magazine.

Sunday, May 26, 2013

Sunday, May 19, 2013

More or Less?

Earlier this week, the Wall Street Journal’s Anne Tergesen wrote a story titled “Mixed bag for auto-enrollment.” Citing data presented at last week’s EBRI policy forum,¹ the article claimed “employees who are automatically enrolled in their workplace savings plans save less than those who sign up on their own initiative.”

She then proceeded to cite Aon Hewitt data presented at the policy forum that illustrated how workers at various salary levels at plans that offered automatic enrollment saved at a lower rate, on average, than workers at the same salary levels at plans that didn’t offer automatic enrollment. The article then went on to note that “The data confirms an analysis EBRI performed for The Wall Street Journal in 2011.”

Well, not exactly.

In a response to an article titled “401(k) Law Suppresses Saving for Retirement” that Tergesen wrote in 2011, EBRI Research Director Jack VanDerhei challenged the premise behind the headline of that article, explaining that it “…suggests that it is actually reducing savings for some people. What it failed to mention is that it’s increasing savings for many more—especially the lowest-income 401(k) participants.”

Not only that, he took issue with the conclusion, explaining that “The Wall Street Journal article reported only the most pessimistic set of assumptions and did not cite any of the other 15 combinations of assumptions reported in the study.”

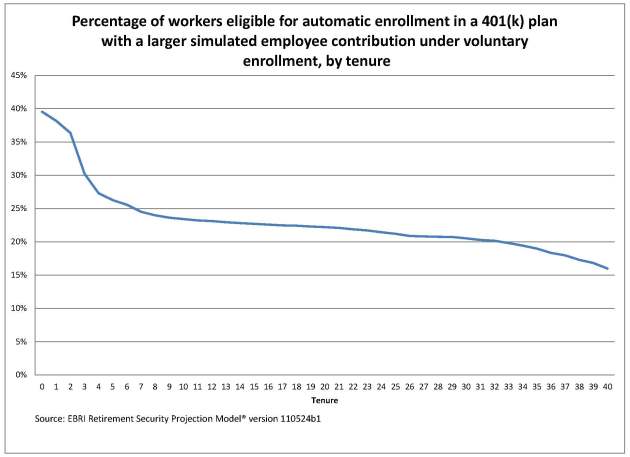

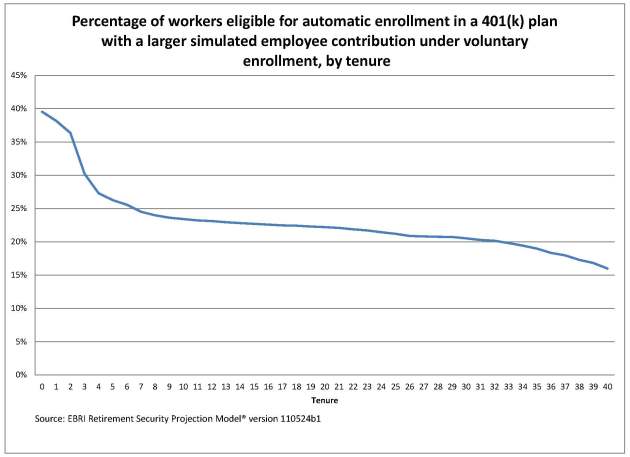

The other statistic attributed to EBRI in the original WSJ article dealt with the percentage of automatic enrollment-eligible workers who would be expected to have larger tenure-specific worker contribution rates had they been voluntary enrollment-eligible instead. The simulation results EBRI provided showed that approximately 60 percent of the AE-eligible workers would immediately be better off in an AE plan than in a VE plan, and that over time (as automatic escalation provisions took effect for some of the workers) that number would increase to 85 percent (see chart below).

Are there those who once might have filled out an enrollment form and opted for a higher rate of deferral (say to the full level of match) that now take the “easy” way and allow themselves to be automatically enrolled at the lower rate adopted for most automatic enrollment plans? Absolutely. However, as the EBRI data show—and, for anyone paying attention, have shown for years now—the folks most likely to be disadvantaged by that lack of action are higher-income workers.

Are there those who once might have filled out an enrollment form and opted for a higher rate of deferral (say to the full level of match) that now take the “easy” way and allow themselves to be automatically enrolled at the lower rate adopted for most automatic enrollment plans? Absolutely. However, as the EBRI data show—and, for anyone paying attention, have shown for years now—the folks most likely to be disadvantaged by that lack of action are higher-income workers.

In fairness, while that 2011 article was titled “401(k) Law Suppresses Saving for Retirement,” the more recent coverage not only characterized automatic enrollment as a “mixed bag,” but acknowledged the “very positive effect on participation rates” as a result of automatic enrollment.

Indeed, the simple math of automatic enrollment is that you get more people participating, albeit at lower rates (until design features like automatic contribution acceleration kick in). Said another way, participation rates go up, and AVERAGE deferral rates dip—at least initially.

That might, in fact, mean that some individuals do, in fact, save less by default² than if they had taken the time to actually complete that enrollment form, or if they fail to take advantage of the option to increase that initial default.

But that ignores the reality (borne out by the data) that many workers will be saving more—because that initial savings choice was automatic.

Nevin E. Adams, JD

¹ Materials from EBRI’s 72nd Policy Forum, including a link to a recording of the event (courtesy of the International Foundation of Employee Benefit Plans) are online here.

² EBRI has recently considered how much difference setting a higher default contribution rate can make in improving retirement readiness. See “Increasing Default Deferral Rates in Automatic Enrollment 401(k) Plans: The Impact on Retirement Savings Success in Plans With Automatic Escalation,” online here.

She then proceeded to cite Aon Hewitt data presented at the policy forum that illustrated how workers at various salary levels at plans that offered automatic enrollment saved at a lower rate, on average, than workers at the same salary levels at plans that didn’t offer automatic enrollment. The article then went on to note that “The data confirms an analysis EBRI performed for The Wall Street Journal in 2011.”

Well, not exactly.

In a response to an article titled “401(k) Law Suppresses Saving for Retirement” that Tergesen wrote in 2011, EBRI Research Director Jack VanDerhei challenged the premise behind the headline of that article, explaining that it “…suggests that it is actually reducing savings for some people. What it failed to mention is that it’s increasing savings for many more—especially the lowest-income 401(k) participants.”

Not only that, he took issue with the conclusion, explaining that “The Wall Street Journal article reported only the most pessimistic set of assumptions and did not cite any of the other 15 combinations of assumptions reported in the study.”

The other statistic attributed to EBRI in the original WSJ article dealt with the percentage of automatic enrollment-eligible workers who would be expected to have larger tenure-specific worker contribution rates had they been voluntary enrollment-eligible instead. The simulation results EBRI provided showed that approximately 60 percent of the AE-eligible workers would immediately be better off in an AE plan than in a VE plan, and that over time (as automatic escalation provisions took effect for some of the workers) that number would increase to 85 percent (see chart below).

Are there those who once might have filled out an enrollment form and opted for a higher rate of deferral (say to the full level of match) that now take the “easy” way and allow themselves to be automatically enrolled at the lower rate adopted for most automatic enrollment plans? Absolutely. However, as the EBRI data show—and, for anyone paying attention, have shown for years now—the folks most likely to be disadvantaged by that lack of action are higher-income workers.

Are there those who once might have filled out an enrollment form and opted for a higher rate of deferral (say to the full level of match) that now take the “easy” way and allow themselves to be automatically enrolled at the lower rate adopted for most automatic enrollment plans? Absolutely. However, as the EBRI data show—and, for anyone paying attention, have shown for years now—the folks most likely to be disadvantaged by that lack of action are higher-income workers.In fairness, while that 2011 article was titled “401(k) Law Suppresses Saving for Retirement,” the more recent coverage not only characterized automatic enrollment as a “mixed bag,” but acknowledged the “very positive effect on participation rates” as a result of automatic enrollment.

Indeed, the simple math of automatic enrollment is that you get more people participating, albeit at lower rates (until design features like automatic contribution acceleration kick in). Said another way, participation rates go up, and AVERAGE deferral rates dip—at least initially.

That might, in fact, mean that some individuals do, in fact, save less by default² than if they had taken the time to actually complete that enrollment form, or if they fail to take advantage of the option to increase that initial default.

But that ignores the reality (borne out by the data) that many workers will be saving more—because that initial savings choice was automatic.

Nevin E. Adams, JD

¹ Materials from EBRI’s 72nd Policy Forum, including a link to a recording of the event (courtesy of the International Foundation of Employee Benefit Plans) are online here.

² EBRI has recently considered how much difference setting a higher default contribution rate can make in improving retirement readiness. See “Increasing Default Deferral Rates in Automatic Enrollment 401(k) Plans: The Impact on Retirement Savings Success in Plans With Automatic Escalation,” online here.

Sunday, May 12, 2013

(Un) Realistic Expectations

This past weekend I joined the throngs of humanity that went to the theaters to see Iron Man 3. I grew up reading Marvel Comics, and, for the very most part, seeing those characters brought to life on the big screen has been a real treat.

I had been curious about the new Iron Man movie for some time, but wasn’t sure if it could live up to expectations based on the prior films. It’s hard to escape the endless promotions for these summer blockbusters, but I made a conscious effort to do so, and even avoided reading the reviews of the film until after I had had a chance to see it for myself. That decision involved some financial “risk” as anyone who has taken a family to the theater recently can attest.

There have, however, been disappointments along the way―sometimes the acting was bad, sometimes the storyline was (unintentionally) laughable, and sometimes the movie fell short of what I had anticipated simply because my expectations were set so high.

Over the years, the Retirement Confidence Survey¹ has helped uncover a number of interesting and intriguing perspectives about retirement, real and imagined―and no small number of what would appear to be unrealistic expectations about retirement: expectations around how long individuals think they will be able to work, for example, or that they will be able to work for pay after retirement. Additionally, there have been indications that more individuals expect to receive a pension than would be suggested by the data regarding how many American workers are actually covered by such programs.

The RCS has found that men and women have similar expectations for the age at which they plan to retire, and that, despite the fact that women tend to live longer and face higher health care expenses in retirement due to their greater longevity, women were statistically as likely as men to think they will need to accumulate less than $250,000 for retirement. More recently, an EBRI analysis indicated that married couple respondents to the RCS were citing retirement savings targets that were better suited for single individuals.²

Much of the focus around the release of the Retirement Confidence Survey was, as one might expect, on retirement confidence―an individual’s sense of their confidence in having enough money to live comfortably throughout retirement. And, despite some of the optimistic assumptions cited above, that confidence was mired at historic lows for the RCS, which has tracked those sentiments for nearly a quarter-century.

Avoiding the incessant summer blockbuster pre-release promotions and commercials takes some effort. In hindsight, going to see the movie with no real expectations beyond that set by prior films was a good decision, certainly from the standpoint of my enjoyment of the newest version.

Admittedly, planning for that financially comfortable retirement can appear a daunting task, one readily shunted aside in favor of more current, and what seem to be more pressing tasks. Despite the ready availability of free planning tools, such as the Ballpark E$timate,³ the RCS indicates that many have never made even a single attempt―have not even guessed―at how much they might need for retirement. Yet EBRI analysis indicates that those who have taken the time to do so set better targets than those who haven’t.

Ultimately, not having established a set of expectations can make for a pleasant surprise at the cinema―but it’s likely to result in a surprise of a completely different sort in retirement.

Nevin E. Adams, JD

¹ The 2013 Retirement Confidence Survey is available online here.

² See “A Little Help: The Impact of On-line Calculators and Financial Advisors on Setting Adequate Retirement-Savings Targets: Evidence from the 2013 Retirement Confidence Survey,” online here.

³ The BallparkE$timate® is available online here. Organizations interested in building/reinforcing a workplace savings campaign can find a variety of free resources there, courtesy of the American Savings Education Council (ASEC). Choose to Save® is sponsored by the nonprofit, nonpartisan Employee Benefit Research Institute Education and Research Fund (EBRI-ERF) and one of its programs, the American Savings Education Council (ASEC). The website and materials development have been underwritten through generous grants and additional support from EBRI Members and ASEC Partner institutions.

I had been curious about the new Iron Man movie for some time, but wasn’t sure if it could live up to expectations based on the prior films. It’s hard to escape the endless promotions for these summer blockbusters, but I made a conscious effort to do so, and even avoided reading the reviews of the film until after I had had a chance to see it for myself. That decision involved some financial “risk” as anyone who has taken a family to the theater recently can attest.

There have, however, been disappointments along the way―sometimes the acting was bad, sometimes the storyline was (unintentionally) laughable, and sometimes the movie fell short of what I had anticipated simply because my expectations were set so high.

Over the years, the Retirement Confidence Survey¹ has helped uncover a number of interesting and intriguing perspectives about retirement, real and imagined―and no small number of what would appear to be unrealistic expectations about retirement: expectations around how long individuals think they will be able to work, for example, or that they will be able to work for pay after retirement. Additionally, there have been indications that more individuals expect to receive a pension than would be suggested by the data regarding how many American workers are actually covered by such programs.

The RCS has found that men and women have similar expectations for the age at which they plan to retire, and that, despite the fact that women tend to live longer and face higher health care expenses in retirement due to their greater longevity, women were statistically as likely as men to think they will need to accumulate less than $250,000 for retirement. More recently, an EBRI analysis indicated that married couple respondents to the RCS were citing retirement savings targets that were better suited for single individuals.²

Much of the focus around the release of the Retirement Confidence Survey was, as one might expect, on retirement confidence―an individual’s sense of their confidence in having enough money to live comfortably throughout retirement. And, despite some of the optimistic assumptions cited above, that confidence was mired at historic lows for the RCS, which has tracked those sentiments for nearly a quarter-century.

Avoiding the incessant summer blockbuster pre-release promotions and commercials takes some effort. In hindsight, going to see the movie with no real expectations beyond that set by prior films was a good decision, certainly from the standpoint of my enjoyment of the newest version.

Admittedly, planning for that financially comfortable retirement can appear a daunting task, one readily shunted aside in favor of more current, and what seem to be more pressing tasks. Despite the ready availability of free planning tools, such as the Ballpark E$timate,³ the RCS indicates that many have never made even a single attempt―have not even guessed―at how much they might need for retirement. Yet EBRI analysis indicates that those who have taken the time to do so set better targets than those who haven’t.

Ultimately, not having established a set of expectations can make for a pleasant surprise at the cinema―but it’s likely to result in a surprise of a completely different sort in retirement.

Nevin E. Adams, JD

¹ The 2013 Retirement Confidence Survey is available online here.

² See “A Little Help: The Impact of On-line Calculators and Financial Advisors on Setting Adequate Retirement-Savings Targets: Evidence from the 2013 Retirement Confidence Survey,” online here.

³ The BallparkE$timate® is available online here. Organizations interested in building/reinforcing a workplace savings campaign can find a variety of free resources there, courtesy of the American Savings Education Council (ASEC). Choose to Save® is sponsored by the nonprofit, nonpartisan Employee Benefit Research Institute Education and Research Fund (EBRI-ERF) and one of its programs, the American Savings Education Council (ASEC). The website and materials development have been underwritten through generous grants and additional support from EBRI Members and ASEC Partner institutions.

Sunday, May 05, 2013

Decision "Points"

There’s a saying that “the best laid plans of mice and men often go astray,” and one need look no further than the experience of a morning commute to see the principle in action.

While we all head to different places from different places, most head out for work at what for each of us is likely a consistent, regular time. That timing may be driven by external or internal factors: a mass transit schedule, by our desire to avoid traffic congestion, the constraints of fellow passengers, or simply by a need to arrive at our place of work at a specific time. But for most of us, on most days, the regularity of that schedule provides a certain dependable start to our days.

It doesn’t take much to disrupt that start, unfortunately—as anyone who has ever awakened to an unexpected snowfall, encountered the impact of a traffic accident on a major thoroughfare, or slept through a snooze alarm can attest. Sometimes we can make up the time loss imposed on our commute, sometimes we simply have to deal with the consequences of being late, and sometimes we make other adjustments in response—a different route, for example, or, if time permits, a different medium of transportation. Sometimes those alternative approaches help matters, and sometimes they don’t.

It doesn’t take much to disrupt that start, unfortunately—as anyone who has ever awakened to an unexpected snowfall, encountered the impact of a traffic accident on a major thoroughfare, or slept through a snooze alarm can attest. Sometimes we can make up the time loss imposed on our commute, sometimes we simply have to deal with the consequences of being late, and sometimes we make other adjustments in response—a different route, for example, or, if time permits, a different medium of transportation. Sometimes those alternative approaches help matters, and sometimes they don’t.

As policy makers, regulators, providers, plan sponsors and individual participants, we make decisions every day that impact not only others, but others’ choices, as well as our own. Sometimes those decisions are not only imposed by external forces, but influenced by factors over which we have little or no control.

On May 9, the Employee Benefit Research Institute will sponsor its 72nd Policy Forum. Titled “Decisions, Decisions: Choices That Affect Retirement Income Adequacy,” the sessions will be looking at factors that matter—both at the macro and micro levels. Specifically, a series of expert panels will consider what a sustained low-interest rate environment means for retirement savings and retirement income, the effect(s) of the match timing, amount, and sources on meeting plan objectives, and helping plans and participants optimize their distribution choices—rollover, drawdown, and annuity options (the agenda is online here).

Every day we make decisions—or have decisions imposed on us. These decisions, in turn, have consequences: some foreseeable, some not, others for which the true impact can only be viewed in the fullness of time. Ultimately, as with a disrupted commute, the better information we have about the nature, size, and duration of the problem, and the alternatives available, the better our choices are likely to be.

That’s what we hope to provide at EBRI’s policy forum next week: insights on key decisions and alternatives, the perspectives of experts, the sharing of research findings, the exchange of ideas.

Even the “best-laid” plans may indeed go astray. All the more reason to have a timely, working appreciation of the alternative(s).

Nevin E. Adams, JD

Information on registering for EBRI’s 72nd Policy Forum is available here. The agenda is online here.

For those unable to attend in person, the EBRI policy forum will be webcast live by the International Foundation of Employee Benefit Plans (IFEBP), online here.

While we all head to different places from different places, most head out for work at what for each of us is likely a consistent, regular time. That timing may be driven by external or internal factors: a mass transit schedule, by our desire to avoid traffic congestion, the constraints of fellow passengers, or simply by a need to arrive at our place of work at a specific time. But for most of us, on most days, the regularity of that schedule provides a certain dependable start to our days.

It doesn’t take much to disrupt that start, unfortunately—as anyone who has ever awakened to an unexpected snowfall, encountered the impact of a traffic accident on a major thoroughfare, or slept through a snooze alarm can attest. Sometimes we can make up the time loss imposed on our commute, sometimes we simply have to deal with the consequences of being late, and sometimes we make other adjustments in response—a different route, for example, or, if time permits, a different medium of transportation. Sometimes those alternative approaches help matters, and sometimes they don’t.

It doesn’t take much to disrupt that start, unfortunately—as anyone who has ever awakened to an unexpected snowfall, encountered the impact of a traffic accident on a major thoroughfare, or slept through a snooze alarm can attest. Sometimes we can make up the time loss imposed on our commute, sometimes we simply have to deal with the consequences of being late, and sometimes we make other adjustments in response—a different route, for example, or, if time permits, a different medium of transportation. Sometimes those alternative approaches help matters, and sometimes they don’t.As policy makers, regulators, providers, plan sponsors and individual participants, we make decisions every day that impact not only others, but others’ choices, as well as our own. Sometimes those decisions are not only imposed by external forces, but influenced by factors over which we have little or no control.

On May 9, the Employee Benefit Research Institute will sponsor its 72nd Policy Forum. Titled “Decisions, Decisions: Choices That Affect Retirement Income Adequacy,” the sessions will be looking at factors that matter—both at the macro and micro levels. Specifically, a series of expert panels will consider what a sustained low-interest rate environment means for retirement savings and retirement income, the effect(s) of the match timing, amount, and sources on meeting plan objectives, and helping plans and participants optimize their distribution choices—rollover, drawdown, and annuity options (the agenda is online here).

Every day we make decisions—or have decisions imposed on us. These decisions, in turn, have consequences: some foreseeable, some not, others for which the true impact can only be viewed in the fullness of time. Ultimately, as with a disrupted commute, the better information we have about the nature, size, and duration of the problem, and the alternatives available, the better our choices are likely to be.

That’s what we hope to provide at EBRI’s policy forum next week: insights on key decisions and alternatives, the perspectives of experts, the sharing of research findings, the exchange of ideas.

Even the “best-laid” plans may indeed go astray. All the more reason to have a timely, working appreciation of the alternative(s).

Nevin E. Adams, JD

Information on registering for EBRI’s 72nd Policy Forum is available here. The agenda is online here.

For those unable to attend in person, the EBRI policy forum will be webcast live by the International Foundation of Employee Benefit Plans (IFEBP), online here.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)